The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande | Summary

Our current world is becoming more complicated in many fields, and the amount and complexity of the knowledge required to operate have exploded. People in various industries are forced to learn more, specialize further, and use new technology, but cannot deal with the complexity and fail.

In the Checklist Manifesto, Atul Gawande shows us how simple checklists can help us deal with the complexities of our personal and professional lives. He makes the compelling argument that checklists will help humans perform better.

Gawande describes his story of using a checklist to improve the medical field. He helped the World Health Organization implement a safe surgery checklist to reduce complications and deaths from surgical operations globally. Gawande also examines the role of checklists in the aviation and construction industry and presents the case for them to be implemented in other sectors.

The Problem of Extreme Complexity

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered Penicillin. This health care innovation seemed like a simple treatment that would cure many illnesses or injuries. Penicillin was effective against several once untreatable infections. However, the medical realm did not become simpler. The past century has had many amazing discoveries that have led to more specialization in health care. Most diseases have required more specific and intricate treatments, even those once simply treated with Penicillin.

Nowadays, treatments vary depending on multiple therapies, the patient’s condition, and the organ systems affected. Thus, medicine has become extremely complex and difficult to master by humans. In the ninth edition of the World Health Organization’s international classification of diseases, there are now greater than 13,000 different diseases, syndromes, and injuries. For most of them, science has found treatments to heal the body. If a cure does not exist, then there is a way to mitigate the damage and impact on the body. However, doctors have to choose between about 6,000 drugs and 4,000 procedures with different specifications, risks, and considerations for any given situation.

This complexity has pushed individuals in the medical field to specialize more and more with many years of training. One needs to have an undergraduate degree, medical degree, and years of residency training. However, there is still an unacceptably large amount of avoidable failures. In the Checklist Manifesto, Gawande asks the question, “What do you do when expertise is not enough?”

The Checklist

In 1935, the US Army Air Corps held a flight competition to win a contract for a new long-range bomber. The Boeing aircraft seemed superior with a larger payload, faster speed, and longer range. In-flight, the Boeing aircraft crashed due to “pilot error” and was deemed too complicated to fly. In response, a few test pilots created a simple checklist for pilots to use at critical stages in flight. The Army ended up ordering almost 13,000 B-17 aircraft, which utilizing a checklist, have flown over a million miles with no incident.

Similarly, significant parts of software engineering, finance, law enforcement, legal work, and medicine have become too complicated. Thus, using a checklist can alleviate complexity. In medicine, doctors use a simple check of four vital signs (body temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory rate), which give workers a good indication of how sick a person is.

Human Nature in Complexity

The Checklist Manifesto discusses two main issues that experts face in a complex environment:

- Humans are fallible when it comes to their memory and attention. These tendencies are very problematic when skipping one step in all-or-none processes such as baking a cake, landing an airplane takeoff, or evaluating a sick patient.

- Humans can tend to skip steps that seem not to matter. One day, a routine-specific action in a complex process may be the difference between success and failure.

Checklists help us prevent catastrophic failure in a world of complexity. They provide us with the minimum viable process and make the steps clear. Checklists allow us to verify our habits and actions and raise our level of performance.

The End of the Master Builder

There are limits to checklists, so it is essential to figure out when they are suitable.

Three Types of Problems

Two professors, Zimmerman and Glouberman, studied the science of complexity and have categorized problems as follows:

- Simple: These issues are like following a recipe. There may be a few basic techniques to learn; however, once learned, following the formula will result in a high probability of success.

- Complicated: These problems are repeatable ones like sending a rocket to the moon. They can be differentiated into a series of simple issues. Success relies on several people and teams with expertise.

- Complex: These problems are difficult ones like raising a child. With children, each one is unique, provides experience, and may require a different approach for success.

Gawande looked to the construction industry for the value of checklists. For most of history, the responsibility of constructing a large building was in the hands of a single Master Builder. They would design, engineer, and manage the entire construction from beginning to end. By the mid-twentieth century, construction became much more complicated, Master Builders disappeared, and specialization occurred, similar to the medical world. The construction industry had to adapt because building failure is not an option as many lives were on the line.

However, hospitals still rely on a leader or “a lone Master Physician with a prescription pad, an operating room, and a few people to follow his lead, plan, and execute the entirety of care for a patient, from diagnosis through treatment.”

In construction projects, workers use various checklists and schedules to overcome complexity. These checklists enabled tracking the progress and prompting communication between several workers. The result is that failure has become very rare at an average of 20 serious “building failures” per year or 0.00002 percent. In the Checklist Manifest, Gawande states that “the checklists work.”

The Idea

In the construction industry, there is a two-checklist approach to dealing with the complexity:

- What: The first checklist detailed the tasks that had to be done and relied on central control from management. These lists ensure that your people don’t overlook the routine, critical aspects.

- How: The second checklist described how to deal with challenging and unforeseen circumstances for workers. These lists ensure communication to deal with issue democratically and measure progress toward project objectives.

This Checklist Manifesto principle forces the decision-making away from management and to the lowest levels. Your people are empowered and are responsible for making decisions and adapting situations based on individual expertise and experience. If you make decisions from the top-down or micromanage, then you will fail in complicated circumstances. If your people fail to communicate with one another, then the isolation will also result in failure.

When people make decisions, there needs to be a balance of freedom and expectation, technique and procedure, and specialization and collaboration. This knowledge is capture in the two opposing types of checklists above. The lists seemed to help in any complicated situation, field, or profession, even the medical field.

The First Try

In 2006, the World Health Organization reached out to Gawande, as he was an expert on patient safety in surgery. The number of surgical operations had escalated worldwide to 230 million per year in 2004, with complications becoming a public danger at an estimated 3 to 17 percent. Thus, the WHO wanted him to lead a team to decrease avoidable deaths and harm from surgery globally.

In 2007, the WHO held a conference for doctors, nurses, and other experts from many backgrounds to determine how to solve the surgery issue. The participants discussed various solutions, including offering incentive pay for practitioners pr publishing surgical care guidelines. However, Gawande discusses his search in the Checklist Manifesto for a simpler solution like using vaccines to eliminate diseases or soap to improve public health. He thought that checklists could be the answer.

After examining the uses of the checklist from three hospitals (Toronto, Hopkins, and Kaiser) for specific issues, Gawande found a theme of fostering teamwork. He wanted to apply checklists universally, so his team created a safe surgery checklist. They included three pause points for the team to work through checks before moving on. In Boston, Gawande found that his surgery checklist was lengthy, unclear, and impractical. His team quickly stopped using it, and he wondered how checklists would ever work globally.

The Checklist Factory

After the first attempt, Gawande went to Daniel Boorman at Boeing to learn about how they wrote checklists for aircraft.

Good vs. Bad Checklists

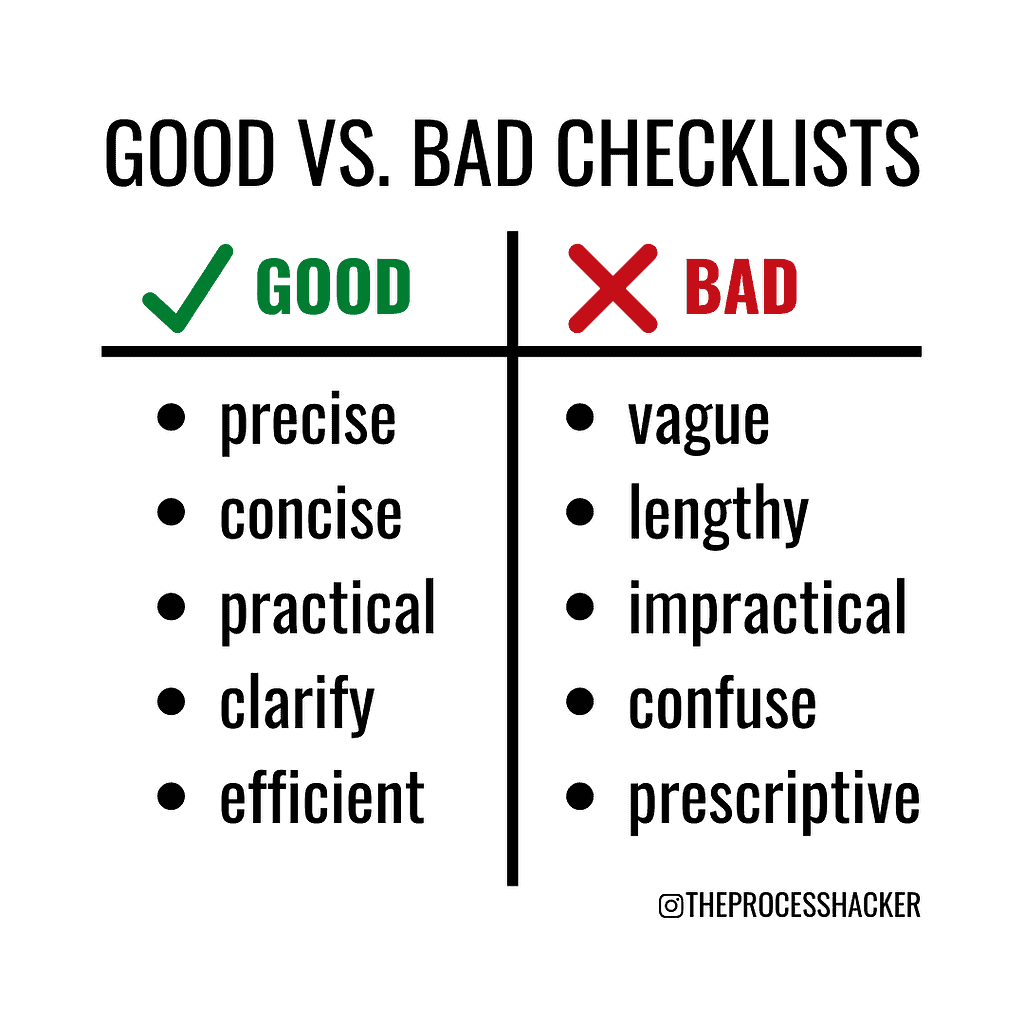

Boorman explained that Checklists could be either good or bad:

- Bad: These checklists are that are vague, lengthy, and impractical. They have been written by desk workers that have not worked in relevant situations. The lists treat workers as stupid, are overly prescriptive, and inhibit critical thinking.

- Good: These checklists are precise, efficient, concise, practical, and wide-ranging. They have been written by practitioners who have experience and expertise. The lists reiterate the most critical steps, clarify priorities, and foster communication.

Two Types of Decision Points

However, checklists still have limitations, as it is tough to make people follow them. Checklists need to include key decision points, in which you have to pause to use the list. You must decide between using the following types per the situation:

- Do-Confirm: “The team members perform their jobs from memory and experience, often separately.” With each pause, they use the checklist to confirm everything that must have been done.

- Read-Do: The team uses the checklist to conduct tasks and check them off one by one like a recipe.

Checklist Rules of Thumb

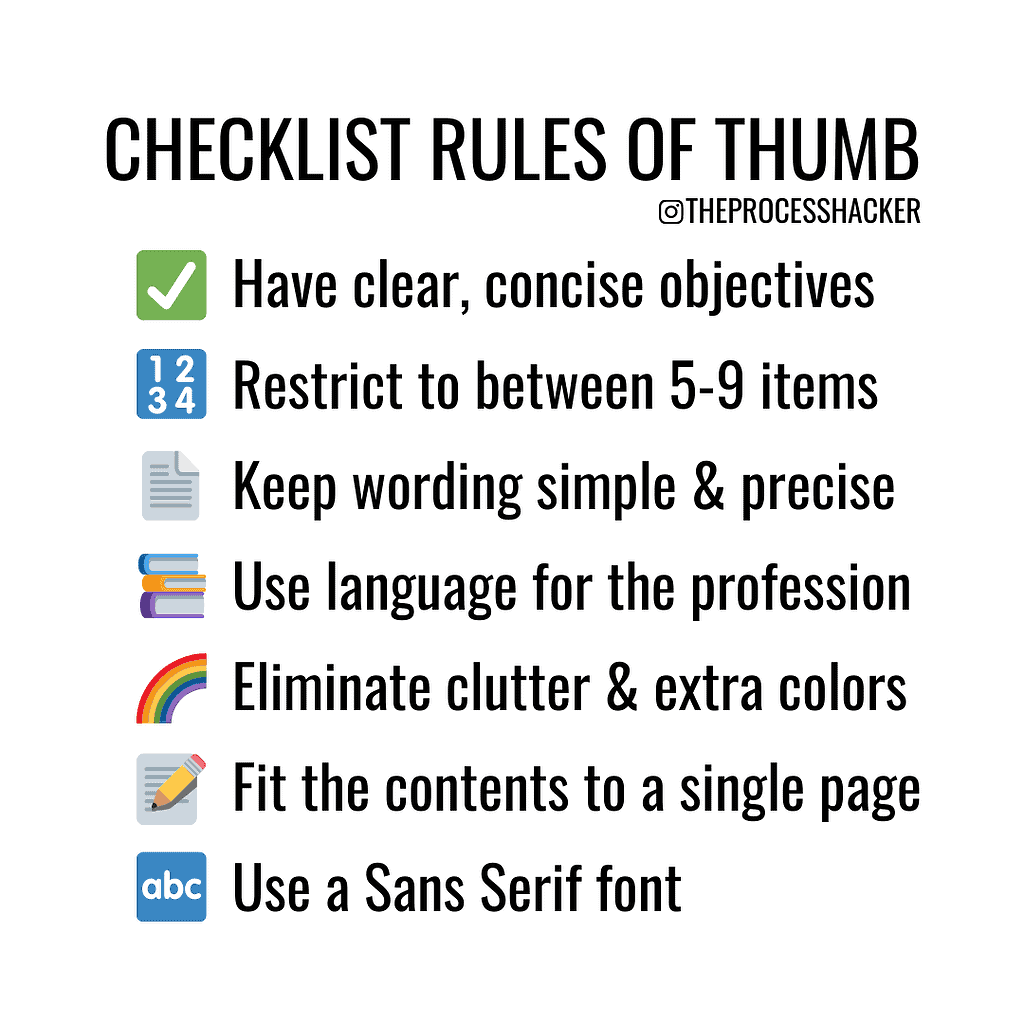

Here are the Checklist Manifesto rules of thumb for creating a Checklist:

- Restrict to between five and nine items, which is the limit of working memory.

- Keep the wording simple, precise, and within the professional vernacular.

- Fit the contents to one page, remove clutter, and eliminate unnecessary colors.

- Use both uppercase and lowercase text with a Sans Serif font for ease of reading.

In complicated professions, checklists are not supposed to be detailed how-to guides but rather a simple tool to supplement your work.

The Test

There seemed to be some hope, so Gawande tried to incorporate aviation lessons to make the surgery checklist useful. After deliberation and testing, the team finalized on a 19-item surgery checklist for the WHO with three pause points:

- Five checks before anesthesia,

- Seven checks after anesthesia and before incision, and

- Five checks before the patient leaves the operating room.

In 2008, eight hospitals from eight different countries tested the safe surgery checklist. “Using the checklist involved a major cultural change, as well—a shift in authority, responsibility, and expectations about care—and the hospitals needed to recognize that.” And it followed that many hesitated using the checklist or threw the observers out of the operating room. However, Gawande found several stories encouraging during testing that are elaborated upon in the Checklist Manifesto.

The final results were better than he expected as the checklist reduced the rate of major surgery-related complications by 36 percent and death by 47 percent. Also, the study found that the list fostered communication, which led to much fewer errors. In 2009, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results, and the interest in the global implementation of the checklist started to grow. Lastly, the study asked the hospital staff whether they would want to use a checklist, and 93 percent said yes.

The Hero in the Age of Checklists

In any effort, there is an opportunity to determine the patterns of failures and establish a checklist to prevent them from occurring. However, it is far from becoming mainstream, especially in the medical field. Gawande discussed that only 12 countries have publically pledged to implement safe surgery checklists in their hospitals. By late 2009, about 10 percent of US hospitals and 2000 other international hospitals had implemented them. There was also an untapped opportunity to further improve the checklist for surgery and adapt it to other specialized medical procedures.

In the 1950s, being a test pilot was heroic but dangerous as there was a 25 percent chance of dying in the job. Over time, checklists and flight simulators helped manage the risks of flying, and pilots lost their hero status. Gawande believes that something similar is happening in medicine to make medical professionals more effective.

Despite the developments that checklists bring, there is still a need for heroic attributes of courage, intelligence, and improvisation. In early 2019, a US flight experienced a bird strike shortly after takeoff, which caused the engines to fail. Known as the “miracle on the Hudson,” Captain Sully and his crew landed the plane safely in the Hudson River, and everyone on board survived. The heroic team remained calm, worked together, followed critical procedures, and improvised when necessary in a very challenging circumstance.

Professional Expectations

The crew was disciplined, but this expectation is missing from most professions. In learned professions, the Checklist Manifesto states that there is a code of conduct with three major expectations:

- Selflessness: We, who accept responsibility for others, will place the needs and concerns of those who depend on us above our own.

- Skill: We will aim for excellence in our experience and expertise.

- Trustworthiness: We will be responsible for our behavior toward our charges.

In aviation, there is a fourth expectation of discipline to follow sound procedures and work well with others. Most professions, especially medicine, value autonomy over discipline; however, we should value discipline in our new world of complexity, high risk, and large enterprises.

Humans are not naturally inclined for discipline, which is why aviation has incorporated checklists to instill discipline. Over time, these checklists have been adapted through safety assessments and aircraft innovation. In other highly complex fields, we have no choice but to give checklists a try.

The Save

Gawande discusses how the checklists have impacted his own surgical operations. In 2007, he started using the safe surgery checklists. He was amazed at how the checklist helped his team catch mistakes or omissions.

Gawande concludes the Checklist Manifesto with the story of how he saved his patient’s life. During a surgical operation, he accidentally created a hole in a major artery, and the patient was losing blood fast. The checklist helped a nurse have sufficient blood to deal with emergencies. The checklist also fostered communication and teamwork as it took the whole team working calmly to save the patient. In the end, the patient survived, was grateful, and was happy for the story to be included in the book.

Next Steps

Checklists can help you deal with the complexities of your personal and professional lives. We can design checklists to help us get more done, reduce mistakes, and delegate easier. I hope this post has inspired you to implement checklists and read The Checklist Manifesto.

If you have any further questions or need additional help, feel free to comment below or send me an email. Also, if you are wanting more Process Hacker content, you can subscribe to our short weekly newsletter on Productivity, Habits, and Resources.